For centuries, vision loss has been considered one of the most irreversible impairments in human health. While several species across the animal kingdom can regenerate damaged eye tissue and fully restore sight, mammals — including humans — have long been thought to lack such restorative abilities. Now, a new study from Johns Hopkins University is challenging that assumption and offering fresh hope that the human brain may hold underexplored mechanisms for recovering lost vision.

Globally, billions of people live with some form of visual impairment, and millions experience near-total or complete blindness. With sight being humanity’s primary sense for navigating and interpreting the world, scientists have spent decades searching for ways to restore damaged vision. While full regeneration of eye cells remains elusive in humans, researchers are increasingly uncovering how the nervous system adapts after injury — and these adaptations may prove to be a crucial stepping stone toward future treatments.

A Different Path to Recovery

Traditionally, neuroscience has held that neurons in the central nervous system do not regenerate once damaged. This belief has shaped how doctors and researchers approach brain and vision injuries. Yet clinical observations have long hinted that something more complex is happening. Many patients show partial recovery of abilities, including vision, after traumatic brain injuries, even when damaged neurons do not regrow.

To investigate this mystery, researchers at Johns Hopkins examined what happens inside the visual systems of mice following injury. Instead of focusing on neuron regeneration, the team studied how surviving cells behave after damage.

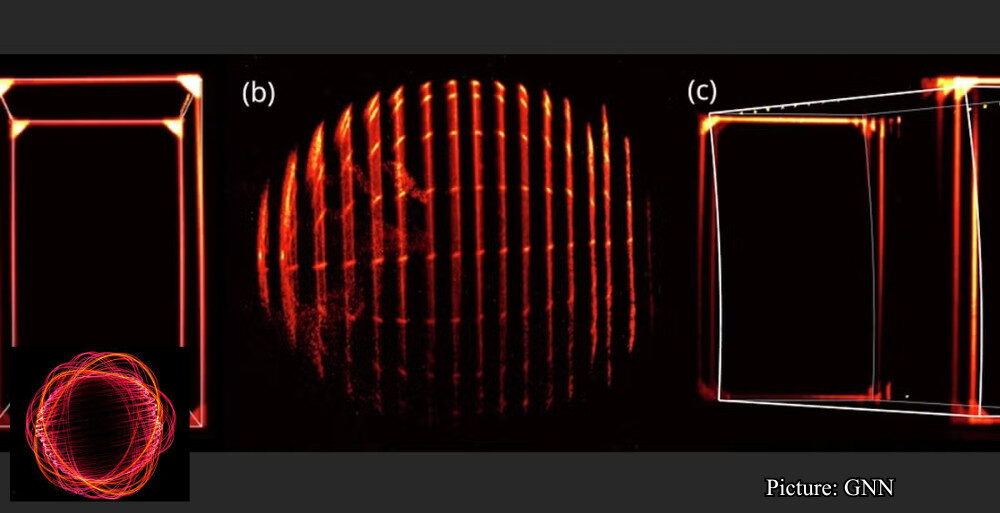

Their findings revealed a remarkable compensatory process. While injured neurons did not regenerate, the remaining healthy cells began increasing their branching — a process known as “sprouting.” This sprouting allowed the surviving neurons to form new connections, gradually rebuilding communication pathways between the eye and the brain.

Over time, this structural reorganization resulted in nearly the same number of neural connections as existed before the injury.

“The central nervous system is characterized by its limited regenerative potential,” the study authors noted, “yet striking examples of functional recovery after injury highlight its capacity for repair.”

The study, published in the peer-reviewed journal JNeurosci, represents one of the first detailed examinations of how the injured mammalian visual system reorganizes itself at a structural level.

Why Sprouting Matters

Rather than replacing lost cells, sprouting enables the brain to reroute signals using existing neural networks. In practical terms, this suggests that the brain may be capable of rewiring itself to restore function — even when full regeneration is impossible.

This discovery shifts the focus of vision research. Instead of asking whether neurons can regrow, scientists are now exploring how neural connections can be enhanced, guided, or accelerated to improve recovery outcomes.

“These findings give us a new framework for thinking about recovery,” said Athanasios Alexandris, lead author of the study. “We’re seeing that the brain can rebuild functional connections even without regenerating damaged neurons.”

A Surprising Gender Difference

One of the most unexpected findings of the study was a clear difference in recovery between male and female mice. Male mice recovered more quickly and more completely after visual system injury, while female mice experienced slower and less complete restoration.

Although the biological mechanisms behind this disparity remain unclear, the observation aligns with existing human data. Women, on average, tend to experience longer-lasting symptoms following concussions and traumatic brain injuries than men.

“Women experience more lingering symptoms from concussion or brain injury than men,” Alexandris explained. “Understanding the mechanism behind the branch sprouting we observed — and what delays or prevents this mechanism in females — could eventually point toward strategies to promote recovery from traumatic or other forms of neural injury.”

This insight could have far-reaching implications, potentially shaping personalized therapies that account for biological sex in neural recovery.

Learning From Nature’s Experts

While mammals rely on compensatory strategies like sprouting, other species possess far more dramatic regenerative abilities. Scientists are increasingly studying animals that can regrow eye tissue to uncover evolutionary clues that might one day be applied to humans.

In recent years, researchers have decoded the genetic mechanisms behind the apple snail’s ability to regenerate its eyes. Separately, another team achieved partial vision restoration in mice by borrowing regenerative strategies observed in zebrafish — a species known for its exceptional neural repair capabilities.

These studies suggest that while humans may not naturally regenerate vision, the biological blueprints for doing so exist elsewhere in nature.

Hope for Future Therapies

Although this research does not offer an immediate cure for blindness, it represents a critical step forward. By understanding how the brain naturally compensates after injury, scientists can begin designing therapies that enhance or accelerate these processes.

Potential future treatments may involve stimulating neural sprouting, protecting surviving neurons, or preventing biological factors that inhibit recovery — particularly in populations that experience slower healing.

For now, full restoration of human vision remains beyond reach. But with each discovery, scientists move closer to unlocking the nervous system’s hidden capacity for repair.

As Alexandris noted, “The answers may already exist within our own biology. We just need to learn how to activate them.”