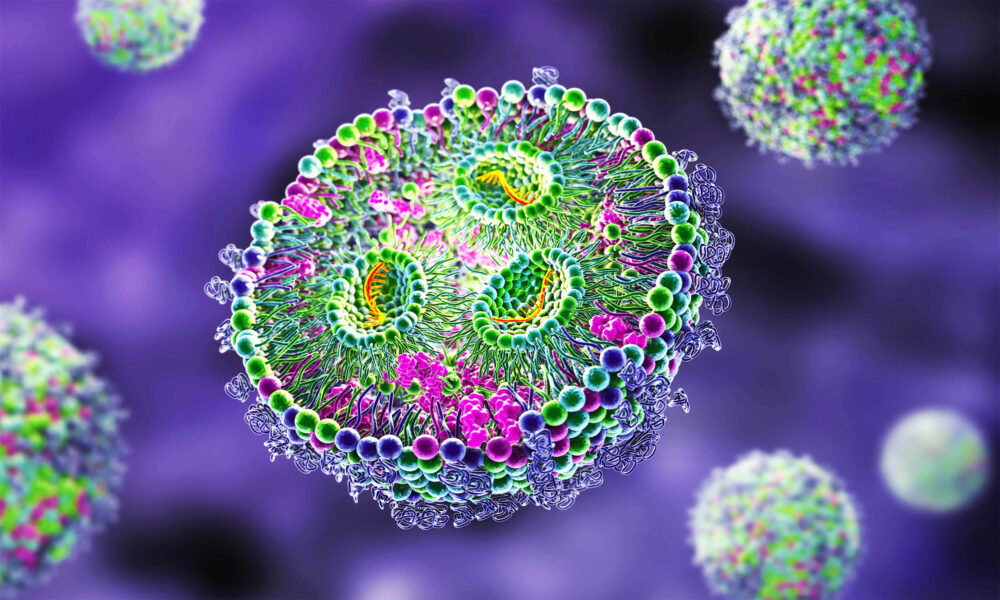

In a discovery that could fundamentally reshape how scientists think about life at its most basic level, researchers have identified a previously unknown class of RNA-based entities living inside bacteria within the human body. These unusual genetic structures, dubbed “obelisks,” do not fit into any known biological category, challenging long-held assumptions about viruses, microbes, and the boundaries of life itself.

The findings emerged from a large-scale analysis of genetic material taken from the human microbiome—the vast ecosystem of bacteria, fungi, and microorganisms that inhabit the mouth, gut, and other parts of the body. Unlike bacteria or viruses, obelisks are composed solely of RNA and appear to replicate without encoding proteins or forming protective shells. Their simplicity, scientists say, is precisely what makes them so intriguing.

“This is something entirely unexpected,” said Andrew Fire, a Nobel Prize–winning biologist at Stanford University who led the research. “We are seeing RNA forms that don’t behave like viruses, don’t act like plasmids, and don’t match anything biology has formally classified so far.”

Thousands of novel RNA loops hiding in plain sight

Using advanced metagenomic tools, the research team analyzed publicly available datasets containing trillions of genetic fragments collected from human-associated microbial communities around the world. Within this sea of data, they identified more than 3,000 distinct types of obelisks, most commonly found in the mouth and intestinal tract.

What sets these entities apart is their structure. Obelisks form closed loops of RNA, lacking the protein-coding regions that define most known viruses. They also show no evidence of producing a capsid—a protein shell typically used by viruses to protect their genetic material. Instead, they resemble viroids, a rare class of circular RNA molecules previously known only to infect plants.

“These RNA loops are remarkably minimal,” the researchers noted in their paper. “They are just genetic information, self-replicating inside bacterial cells, without any of the machinery we usually associate with life.”

The study was published as a preprint on bioRxiv, an open-access platform that allows scientists to share early findings before formal peer review. Even at this preliminary stage, the work has generated intense interest among microbiologists and evolutionary biologists.

Embedded in bacteria, yet not part of them

Careful filtering was used to rule out sequencing errors or laboratory contamination. After removing artefacts, researchers found that many obelisks were consistently associated with specific bacterial hosts, suggesting a long-term relationship rather than random occurrence.

“These structures appear to replicate within bacteria that play important roles in digestion and immune regulation,” said one of the study’s co-authors. “While we haven’t linked them to any disease or health condition, their presence inside such critical microbes means we need to understand what they’re doing.”

So far, no evidence suggests obelisks directly harm humans. However, scientists caution that subtle interactions—such as influencing bacterial behavior or gene expression—cannot yet be ruled out.

A challenge to how life is defined

Obelisks sit in an uncomfortable gray zone for biologists. They are not alive in the traditional sense—lacking cells, metabolism, and proteins—yet they clearly replicate and evolve, two hallmarks of life.

Because of this, the discovery has implications far beyond microbiology. Some researchers see obelisks as potential living analogues of early Earth, when life may have relied entirely on RNA before the evolution of DNA and proteins.

“This adds weight to the idea that RNA-only systems can persist in complex ecosystems,” noted a review in Royal Society Open Science, which recently highlighted emerging research on unconventional RNA replicators. “It forces us to rethink what forms life can take.”

Interestingly, different variants of obelisks appear in different parts of the body, suggesting they may adapt to local microbial environments. Whether this reflects competition, cooperation, or simple coexistence with bacterial hosts remains unknown.

What this means for future research

The discovery underscores the power of modern genomic tools. Advances in sequencing and bioinformatics now allow scientists to detect genetic entities that were completely invisible just a decade ago.

Researchers including Mark Peifer and Matthew Sullivan, who work on host–microbe interactions and viral ecology, say findings like this highlight how little is still known about the microbial world living inside humans.

“Every time we look more closely, we find something that doesn’t fit our models,” Sullivan has previously noted in related research. “That’s both humbling and exciting.”

Scientists are now racing to answer key questions: How are obelisks transmitted between bacteria? Do they influence microbial ecosystems in subtle ways? And are they ancient relics from the dawn of RNA-based life—or modern molecular parasites that evolved alongside humans?

For now, obelisks remain biological enigmas. But their discovery sends a clear message: even within our own bodies, life still holds profound and surprising secrets.