“The life of Guru Gobind Singh offers a model for meeting cultural conflict not with otherness, but with an intentional and revolutionary oneness.”

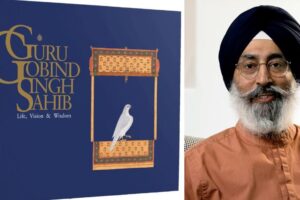

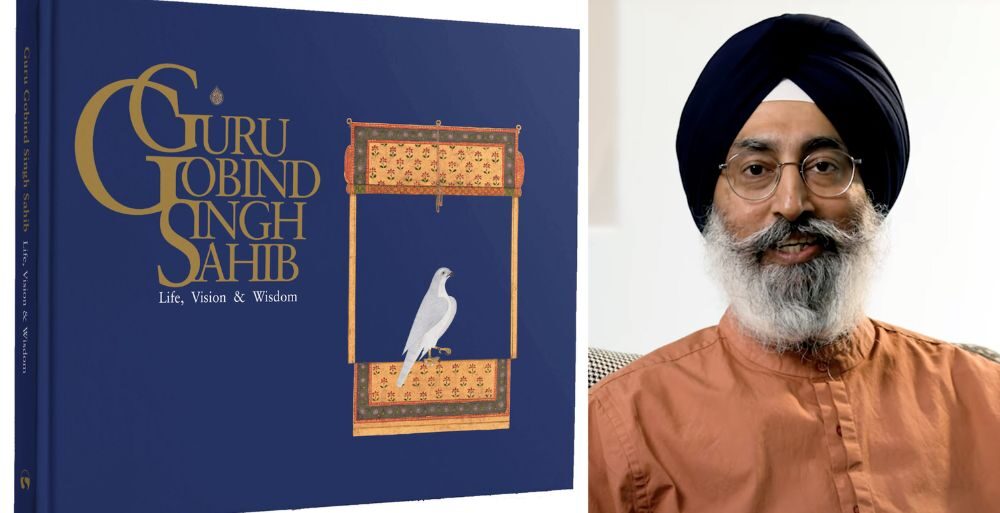

Harinder Singh, a senior fellow at the Sikh Research Institute, has released a seminal work titled “Guru Gobind Singh Sahib: Life, Vision & Wisdom,” aiming to redefine the global understanding of the Tenth Guru. As the Sikh community approaches the 350th anniversary of Guru Gobind Singh’s coronation, this new volume arrives at a critical juncture for a faith that now counts nearly 30 million adherents worldwide. The Guru, who was the final human leader in a lineage that spanned two and a half centuries, is perhaps best known for installing the Guru Granth Sahib as the eternal scriptural guide for all Sikhs. However, Singh argues that the nuances of the Guru’s intellectual and spiritual contributions have often been overshadowed by a narrow focus on his military exploits.

The publication is the result of a meticulous collaborative process involving calligraphers and graphic designers. By eschewing traditional portraiture—which Singh notes are often purely imaginary constructs—the book utilizes poetic text and contemporary translations of original manuscripts. These include works by the Guru’s own court poets, such as Bhai Nand Lal Goya and Chandra Sain Sainapati, written in Persian, Braj, and old Punjabi. This focus on calligraphy and poetry is intentional, designed to shift the reader’s focus toward the “wisdom” and “vision” of the leader rather than a static physical image. Singh posits that the Guru’s true form exists in the concentration of the mind on his teachings, rather than in visual icons.

One of the most striking arguments presented in the book is the characterization of Guru Gobind Singh as the “first diaspora guru.” Born in Patna, outside the traditional Sikh heartland of Punjab, the Guru was shaped by various civilizations across South Asia. This diverse upbringing, according to Singh, allowed the Guru to navigate cultural conflicts with a philosophy of oneness. In a modern era marked by deep political and social polarization, this perspective offers a roadmap for contemporary readers seeking to bridge the divide between disparate identities. The Guru’s life serves as a historical precedent for global citizens navigating multiple cultural spheres simultaneously.

Singh identifies a pervasive stereotype that has limited the public’s perception of the Tenth Guru for over a century: the image of the “warrior-guru.” While the Guru was indeed a leader of the Khalsa—the initiated Sikh community—Singh argues that the “martial race” narrative is a colonial construct later adopted by Indian nationalism. This reductionist view, often used for political appropriation, fails to account for the Guru’s role as a patron of the arts and a scholar who trained his followers to be “warriors who are not fighters.” The distinction is subtle but vital; the Guru sought to chisel individuals into poets and thinkers who were capable of defending justice, rather than mere combatants.

The book also delves into the Guru’s pioneering model of representative democracy. When the leadership of the Sikh community was transitioned to the Khalsa, the first five initiates hailed from diverse regions across South Asia, including Gujarat and other non-Punjabi areas. Singh describes this as a “true nation-building project” in the modern sense of the term. By dismantling the hierarchies of caste and geography, the Guru established a system based on voluntary participation and radical equality. This historical context provides a sharp contrast to the conquest-driven narratives that dominated much of South Asian history during the same period.

Reflecting on his own personal journey, Singh shares how his relationship with the Guru evolved from “hero worship” during his youth in Uttar Pradesh and Kansas to a more profound, intellectual connection. In his teenage years, the Guru functioned as a cultural superhero, comparable to figures like Superman. However, through rigorous research and study, Singh transitioned toward seeing the Guru as an “uncontested leader” whose contributions were grounded in specific religious and political contextualization. This evolution highlights a central theme of the book: moving beyond the “icon” to engage with the actual substance of the Guru’s life and work.

The relevance of Guru Gobind Singh’s teachings to modern Western society is a core focus of the later chapters. Singh asserts that the Guru’s wisdom transcends the artificial divides of East versus West or medieval versus modern. He argues that the Guru sought to integrate the political and the spiritual within the individual, creating agents of love and justice. This integration is presented as a solution to the “otherness” that plagues contemporary discourse, whether in the context of the Modi administration in India or the political landscape of the United States under figures like Donald Trump. The philosophy of oneness, as taught by the Tenth Guru, is not a vague concept but a specific, unitary practice aimed at eliminating polarities.

The inclusion of original art and contemporary translations serves to make the Guru’s 17th-century wisdom accessible to a 21st-century audience. By focusing on the intellectual output of the Guru’s court, the book highlights a period of intense creativity and philosophical inquiry. Singh notes that the Guru’s court was a sanctuary for poets and thinkers, reflecting a commitment to intellectualism that is often lost in modern portrayals. The book aims to reclaim this legacy, presenting the Guru as a visionary who prioritized the development of the mind and spirit as much as the protection of the community.

Ultimately, Singh’s work is intended for two distinct audiences. For Sikhs, it offers a deeper dive into the specific thoughts and writings of their leader, moving beyond the slogans often found in popular culture. For non-Sikhs, it provides an essential introduction to a figure who is frequently referenced but rarely understood in full. By addressing the “otherness” found in sexuality, caste, religion, and colorism, the book positions the Tenth Guru’s teachings as a timeless intervention against the afflictions of the human condition. It is a call to move toward a specific, non-debatable oneness that recognizes the inherent dignity of all people.

As the Sikh Research Institute continues to promote education and awareness, Singh’s biography stands as a comprehensive resource for those wishing to understand the historical and spiritual foundations of Sikhism. It challenges the reader to look past the symbols—the sword, the turban, and the martial history—to find a leader who was deeply invested in the art of the soul. Through this shift in narrative, the Tenth Guru is reimagined not just as a figure of the past, but as a guide for a globalized future where the integration of the spiritual and the political remains more necessary than ever.