New research reveals that a narrow observational focus on air pollutants leads to significant miscalculations in radical budgets, masking the true drivers of persistent ground-level ozone.

A multi-institutional study published in January 2026 has uncovered a critical gap in atmospheric modeling that explains why ground-level ozone remains a persistent threat despite aggressive efforts to reduce traditional pollutants. The research, featured in the journal Environmental Science and Ecotechnology, suggests that Oxygenated Volatile Organic Compounds (OVOCs) play a far more dominant role in ozone formation than previously understood. By failing to account for a broad spectrum of these reactive intermediates, current air quality models may be fundamentally misrepresenting the chemical pathways that lead to smog, thereby complicating environmental mitigation strategies worldwide.

Ground-level ozone is a secondary pollutant formed through complex photochemical reactions involving nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds in the presence of sunlight. Unlike the protective ozone layer in the stratosphere, ozone at the surface level is a potent respiratory irritant and a greenhouse gas that damages ecosystems and reduces crop yields. Despite decades of regulation targeting primary emissions, many urban and industrial regions continue to see ozone levels that exceed health standards. This study, led by researchers from the Southern University of Science and Technology and The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, aimed to resolve this paradox by examining the “hidden” chemistry of the background atmosphere over southern China.

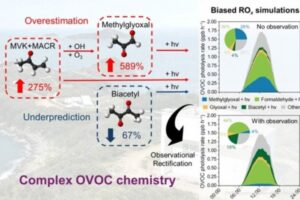

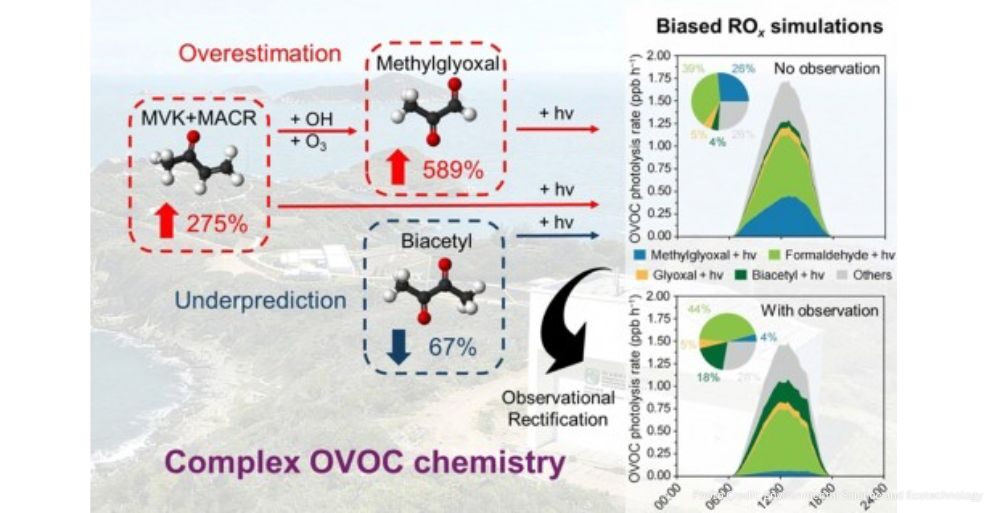

The research team combined high-resolution field observations with an advanced photochemical box model to analyze radical cycling—the engine that drives ozone production. Radicals, such as the hydroxyl radical, act as the “detergents” of the atmosphere, but they also trigger the chemical chain reactions that generate ozone. The study found that most standard models rely on measurements of only a handful of OVOCs, such as formaldehyde or acetaldehyde. When the researchers constrained their model using only these common markers, they found that simulated hydroxyl radical levels were overestimated by as much as 100 percent. This massive discrepancy suggests that many existing air quality predictions are built on a flawed understanding of atmospheric radical budgets.

+1When the team expanded their scope to include a wider array of 23 different OVOCs, the simulations aligned closely with real-world observations. The analysis revealed that the photolysis, or light-driven breakdown, of these compounds contributed between 49 and 61 percent of total radical production in background air. This makes OVOCs the primary source of radicals in these environments, surpassing more traditionally studied precursors. Notably, the study found that even OVOCs present in relatively low concentrations exerted a disproportionate influence on the atmosphere’s oxidative capacity. Small errors in accounting for these minor compounds were shown to cause cascading biases, leading to incorrect conclusions about how ozone is formed and how it should be controlled.

One of the most concerning findings of the study is that traditional chemical mechanisms often contain “offsetting errors.” Models may appear to provide accurate ozone predictions because they overestimate certain OVOCs while underestimating others. However, these hidden inaccuracies mean the models fail when atmospheric conditions change or when specific emission controls are implemented. This masking effect can lead policymakers to believe that ozone production is sensitive to one type of pollutant when it is actually driven by another, resulting in expensive regulatory strategies that fail to produce the desired improvements in air quality.

Senior authors of the study emphasized that what remains unmeasured in the atmosphere often matters more than what is currently monitored. Treating OVOCs as mere secondary byproducts of other pollutants is no longer a viable approach for sophisticated air quality management. The researchers argue that without comprehensive observations that capture the full diversity of oxygenated compounds, models will continue to appear accurate while fundamentally misrepresenting the underlying physics and chemistry of the air we breathe. Expanding the monitoring networks to include these reactive intermediates is now considered an essential step for regions struggling with chronic pollution.

The implications of this research are global. As industrialized and developing nations alike struggle with the “ozone paradox,” the study provides a roadmap for more effective intervention. Current strategies focused solely on reducing nitrogen oxides or primary volatile organic compounds may be insufficient if the radical chemistry driven by OVOCs is ignored. By updating chemical mechanisms and expanding the suite of tracked pollutants, environmental agencies can improve the accuracy of their predictive tools and identify more successful pathways for mitigation. This shift in focus is particularly relevant for the design of “ozone-season” regulations and the development of long-term climate action plans.

The study also highlights the importance of international scientific collaboration in tackling atmospheric challenges. The research involved experts from Hong Kong Baptist University, Beijing University of Chemical Technology, and the University of Helsinki, reflecting a cross-border effort to solve a problem that does not respect national boundaries. This collaborative approach allowed the team to utilize diverse data sets and sophisticated modeling techniques that would have been difficult to coordinate within a single institution. The resulting data provides a robust foundation for the next generation of atmospheric research.

Environmental Science and Ecotechnology, the journal that published the findings, is a leading peer-reviewed venue for research at the intersection of ecology and environmental engineering. With an impact factor of 14.3, the journal frequently highlights studies that have direct applications for sustainability and public health. The publication of this study coincides with a renewed global interest in “green catalysis” and AI-driven environmental modeling, both of which are increasingly used to process the high-resolution data sets required to track complex chemicals like OVOCs in real-time.

Ultimately, the researchers conclude that recognizing the hidden role of oxygenated compounds is the key to resolving the long-standing challenge of persistent surface ozone. As monitoring technology becomes more affordable and sensitive, there is a growing opportunity for cities to integrate these findings into their local air quality networks. Moving toward a more comprehensive observational framework will allow for a more nuanced understanding of how human activity interacts with natural atmospheric processes. By pulling back the curtain on invisible chemistry, this study offers a clearer path toward achieving truly clean air for populations around the world.

In the coming years, the research team plans to expand their observations to different geographic regions, including urban centers and maritime environments, to see if the dominance of OVOCs holds true across various conditions. They also hope to work with policymakers to ensure that the next generation of air quality standards reflects the complex realities of radical cycling. As the world continues to industrialize and the climate changes, understanding these invisible chemical drivers will be more important than ever for protecting both human health and the global environment.